As political shifts and crackdowns in the Gulf prompt producers in Syria and Lebanon to explore new markets, Europe is preparing for the potential surge of a drug that has ensnared the Middle East.

Individuals and groups connected to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and his ally, the Lebanese militia Hezbollah, primarily produce and traffic the amphetamine-type pill captagon, which sells for around $3 to $25 per tablet. This information comes from the US State Department, Treasury, the UK’s Foreign Office, and independent researchers.

Already popular in parts of the Middle East with everyone from teenagers to low-income construction workers, the narcotic is easy to make. Called “the poor man’s cocaine”, it’s reported to trigger bursts of energy and productivity, wakefulness, euphoria as well as delusions and a sense of invincibility. The pill has also been associated with militants in Iraq and Syria.

Two leading researchers at the think tank New Lines Institute estimate that captagon has generated business worth as much as $10 billion over the past three years, with most of the revenue benefiting Assad’s inner circle and allies, who remain heavily sanctioned by the West over their bloody quelling of Syria’s 2011 uprising. Assad and his government deny involvement in the manufacture and trade of captagon.

But now captagon is likely to become a threat for Europe and the rest of the world too, warn officials and experts. A crackdown by the Saudis coupled with their recent efforts to reengage Assad in order to curb flows of the drug is spurring producers to develop new routes and markets, experts say.

“Like any illicit economy, these traffickers and smugglers are becoming much more sophisticated and advanced in trying to target new transit markets, identify new routes, and then also try and carve out new consumption markets,” said Caroline Rose, a director at the New Lines Institute, where she leads a research project on captagon trade. “They’re adapting and adopting new methods.”

Two senior European Union officials who spoke on condition of anonymity said that intelligence reports they have seen and briefings they received from counterparts in the Middle East suggest it’s very likely that captagon flows into Europe will intensify, driven by Syria’s need for cash and Assad’s desire to export addiction and social tensions to countries that in his view harmed him.

Like the US, European powers first backed popular protests against Assad and then supported political dissidents and rebel groups that have sought to topple him.

The officials, who chose not to reveal their names due to the sensitive nature of the matter, stated that while captagon has yet to pose a problem in Europe, policymakers and security officials across the continent are growing increasingly concerned about the issue and have it on their radar.

In an interview with Sky News Arabia last week Assad said war, weak governance and corruption have turned Syria into a “flourishing” base for captagon manufacturing and trade but denied involvement by him or his government. He said responsibility lay with Western and regional states which “sowed chaos in Syria” by intervening on his opponents’ side.

New Markets

Europe risks experiencing the same scenario that has played out in Iraq and Turkey, according to the New Lines Institute’s Rose, noting that those two countries were popular trans-shipment points for captagon but are now becoming destination markets. Iraqi authorities announced in early August that they had busted a key network after discovering the first captagon factory in July.

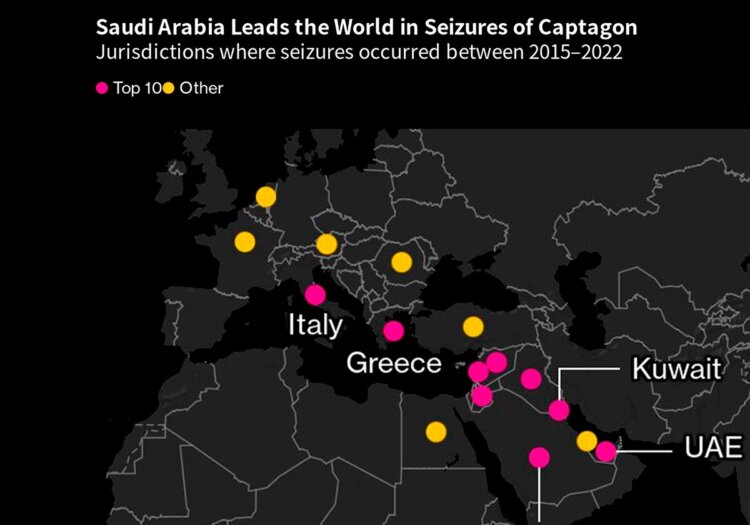

The threat, she said, is not just to countries in Europe’s periphery like Greece and Italy, where authorities seized more than 14 tons of captagon in 2020, but also in the center and north where there have been numerous captagon warehouse raids in recent years.

In 2021, Austrian investigators coordinating with counterparts on four continents broke up a transnational gang bringing in captagon pills from Lebanon and Syria to Europe. The drug ring, which used a pizzeria in Salzburg as one of its hubs, was shipping captagon to Saudi Arabia inside pizza ovens and washing machines. The smugglers’ rationale was that the Saudis were less likely to search cargo from Europe.

As narcotics find new routes for trafficking, the drug itself serves as payment in kind to certain intermediaries, posing a risk of spillover into the local market. This insight comes from a senior official knowledgeable about the perspectives of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

The expanding scope of the captagon trade is also alarming the US.

Two US lawmakers introduced a bill in July to issue new sanctions against Assad with one of them describing him as “a transnational drug kingpin.” In June, the Biden administration released its strategy to “disrupt, degrade, and dismantle the illicit captagon networks linked to the Assad regime” as mandated by the “Captagon Act” passed last year.

This year, Brussels, London and Washington imposed sanctions on Syrian and Lebanese individuals including three cousins of Assad they accused of mass producing captagon.

The drug first appeared in the early 1960s in Germany as an authorized pharmaceutical under the trade name “Captagon.” Its main ingredient was fenethylline and it was prescribed for a range of conditions including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, both Syria and Lebanon began to emerge as production centers in the 2000s. After brutally suppressing a popular uprising against Assad, the production witnessed a surge, leading to a war that involved regional and global powers as well as extremist groups. Gulf Arab states have been the biggest market for captagon over the past two decades.

A Billion Pill

Saudi Arabia stands out as a cautionary tale of what captagon can do to a society.

In the past three years, authorities have confiscated over 1 billion captagon pills, with the majority intended for the kingdom. This information comes from Karam Shaar, a Syrian economist and researcher who has provided counsel to Western governments regarding Syria’s war economy.

A Saudi medic at a unit of a Riyadh public hospital treating addiction and overdose called the situation dire, with adolescents often rushed in after taking 10 or 15 captagon pills. He’s seen users move to more harmful synthetic drugs like crystal meth. Attempts to reach officials at the Saudi interior and health ministries were unsuccessful.

A senior Saudi official, who requested anonymity, expressed concerns that if left unattended, captagon consumption and the broader drug issue could jeopardize Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 economic transformation plan, which relies on empowering the youth. About 63% of the population is under the age of 30, and MBS is personally overseeing what Saudi authorities describe as a war on drugs.

The drug’s popularity extends far beyond Saudi Arabia, with usage observed from the United Arab Emirates to Jordan, where the army has been mobilized to combat the captagon trade. Ending captagon smuggling from Syria and Lebanon topped the agenda of a meeting of Arab foreign ministers in Cairo on Tuesday.

‘Diplomatic Tool’

In last week’s interview, Assad seemed to make the lifting of European and US sanctions on Syria and funds to rebuild the economy a precondition to any progress in fighting captagon or allowing Syrian refugees to return homes.

Assad’s deploying captagon as a “diplomatic tool” to try to secure financial support from Saudi Arabia and sanctions relief from the West, said Lina Khatib, director of the SOAS Middle East Institute, who gave testimony to British lawmakers in June.

For more, read: Saudis, UAE Lobby Europeans to Restore Ties With Syria’s Assad

Michel Duclos, a former French ambassador to Syria currently affiliated with the Institut Montaigne and Atlantic Council, said Assad is using captagon as a bargaining chip just as his father Hafez used covert support for Middle Eastern terrorist groups between the 1970s and 90s.

Finance

Finance